I confess. I want to know everything about them, from how they drink their coffee to their philosophy of life. I want to hear the details of their daily routine. I want to know their favorite books and music. I want to see pictures of them walking their dog, having drinks in a cafe, holding hands with their partner. I want to know what makes them tick, what turns them on, what inspires them, what lifts them from the depths of despair.

The “rich and famous” I’m referring to are NOT rock stars or box office idols...at least they wouldn’t be considered so to anyone else. No, the people whose lives I’m eager to peek inside are those writers, poets, musicians, and artists whose creative genius astounds and delights me.

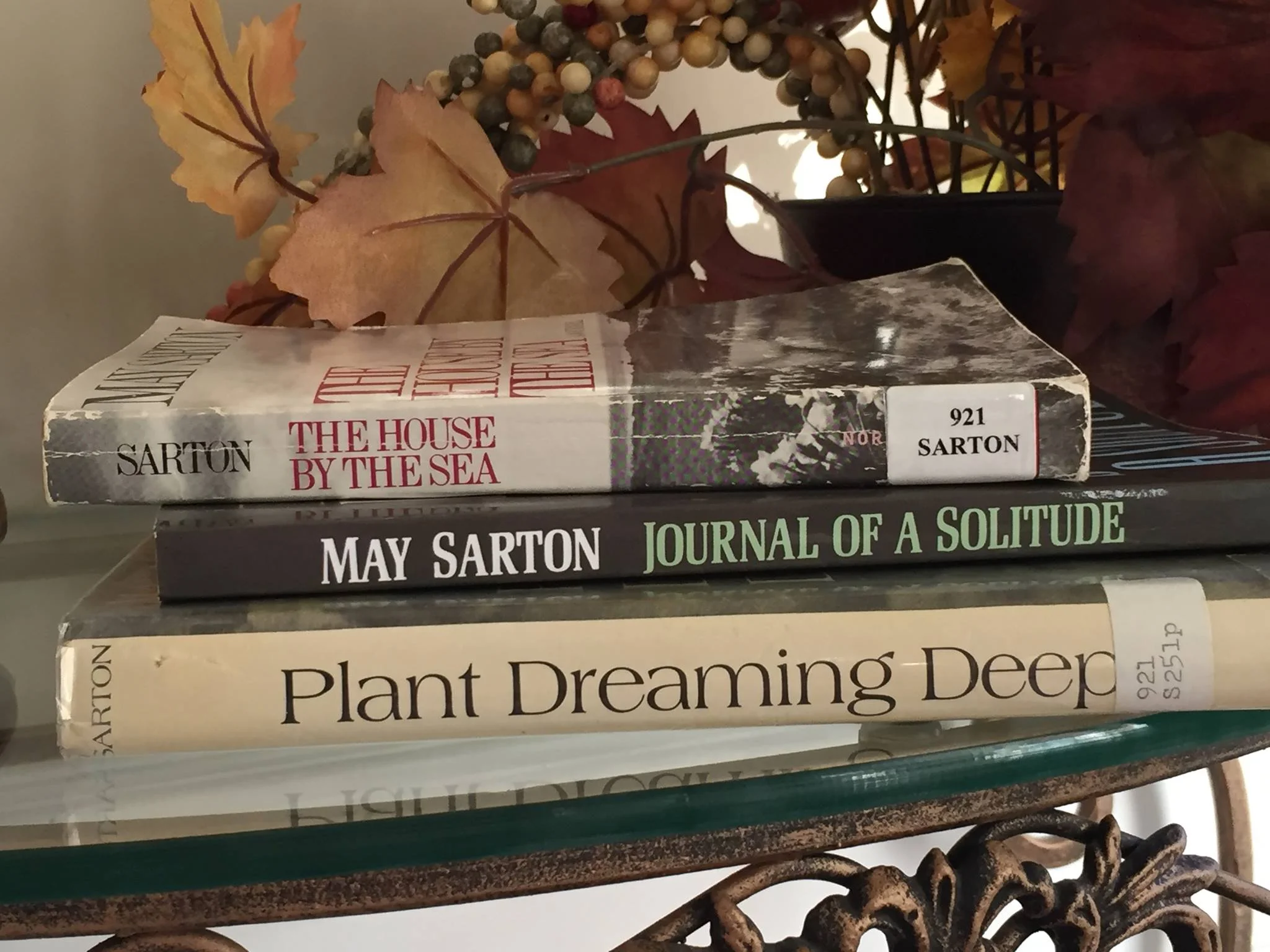

This is the obsession that drives my love of memoir and journals, one I’ve been feeding for the past month by delving into the journals of May Sarton, a 20th century American poet and novelist with a major opus, but one who isn’t perhaps as well known as she might be. As I’ve been immersed in Sarton’s journals, I’m continually struck by several threads of common thought in this work that seem timeless and true, at least for me.

Sarton writes incessantly about the continual push-pull between creative energy and the demands of “real life,” sentiments that echo through the personal writing of every woman author I’ve ever read, from Edith Wharton to Virginia Woolf to Anna Quindlen. “I am leading a cluttered life these days,” Sarton writes in Journal of a Solitude. “Clutter is what silts up exactly like silt in a flowing stream when the current, the free flow of the mind, is held up by obstruction. I spent four hours in town getting the car inspected and two new tires on, also finding a few summer blouses. The mail has accumulated in a fearful way, so I have a huge disorderly pile of stuff to be answered on my desk. Punch (her bird) has a huge swelling over his left eye, and he may be going blind...I have to get him to a vet. In the end what kills is not agony (for agony at least asks something of the soul) but everyday life."

This stuff of everyday life never changes - no matter our place or time in history. Sarton’s journals cover a period of about 30 years, from the mid-1960’s up to her death in 1995. She often writes about “the times” she lives in, sharing sentiments that are familiar to my own thoughts in the past decade. “Everything has become speeded up and overcrowded,” she writes in 1972. “It becomes harder and harder to find space and time around me. Everything that slows us down and forces patience, everything that sets us back into the slow cycles of nature, is a help." In 1977 Sarton laments the state of the world: “It seems possible that we are returning to a Dark Age. What is frightening is that violence is not only represented among nations (at war), but everywhere walks among us freely."

And yet, just as I and so many others do, Sarton finds refuge in her solitude, her routine, her home. “From where I sit at my desk I look through the front hall, with just a glimpse of staircase and white newel post, and through the warm colors of an Oriental rug on the floor of the cosy room, to the long window at the end that frames distant trees and sky from under the porch roof where I have hung a feeder for woodpeckers and nuthatches. This sequence pleases my eye and draws it out in a kind of geometric progression to open space. Indeed, it is just the way rooms open into each other that is one of the charms of the house. People often imagine I must be lonely. How can I explain? I want to say, ‘Oh no! You see the house is with me.’”

Sarton’s largest and perhaps most familiar struggle is to slow down, to “throttle back” as I sometimes advise myself when I allow myself to be sucked into the vortex of busy-ness that characterizes everyday living and all its expectations. “I always forget how important empty days are,” Sarton reminds herself (and us as well) “how important it may be sometimes not to expect to produce anything, even a few lines in a journal. I am still pursued by a neurosis about work inherited from my father. A day where one has not pushed oneself to the limit seems a damaged day, a sinful day. Not so! The most valuable thing we can do for the psyche, occasionally, is to let it rest, wander, live in the changing light of a room, not try to be or do anything whatever."

Sarton wrote nine “journals” which were originally written with the intent to publish, unlike many other authors’ published journals which were edited and compiled after their death by a literary executor. This format interests me. While some might consider it narcissistic, might call it posturing, I find it refreshing. It invites us to look at the moment-to-moment of life a little differently, to elevate the present experience into something worth preserving for what it might teach us - both writer and reader - in retrospect.

Perhaps in the end this is what interests me most about the “lives of the rich and famous” - the places where our journey intersects: Where their struggles mimic mine, where their discoveries enlighten me, and where their experiences validate my own.

Books referenced in this post: